2.3. Hazard Characterization

Both the wind and flood hazards affect the building inventory in this testbed. As the initial implementation of the regional assessment workflow incorporates the HAZUS Hurricane Damage and Loss Assessment methodology, hazards are quantified by two intensity measures: Peak Wind Speed (PWS) and Peak Water Depth (PWD). The PWS refers to the maximum 3-second gust measured at the reference height of 10m in open terrain (equivalent to Exposure C in ASCE 7-16). The PWD is the maximum depth of flooding (height of storm surge above grade) during the storm.

The following sections will introduce the options for generating these two types of hazard inputs using either a historical scenario or a synthetic storm scenario, as discussed in the following sections. Note that as part of the Asset Representation Process (see Asset Representation), the design wind speeds from ASCE 7 are already included for each building footprint for reference.

2.3.1. Synthetic Storm Scenario

An Atlantic City landfall scenario was generated using the Storm Hazard Projection Tool developed in the NJcoast project ([NJCoast20]). The constructed hazard scenario uses NJcoast’s basic simulation option, which identifies the 25 hurricane tracks from the SHP tool’s surrogate model that match the targeted storm scenario, in this case: a hurricane with Category 5 intensity (central pressure differential of 75-100 mbar, radius of maximum winds of 15.4 to 98 mi) making landfall near the Atlantic City Beach Patrol Station (39.348308° N, -74.452544° W) under average tides. This scenario is sufficient to inundate coastal areas in the testbed geography and generate significant wave run-up in some locales. The SHP Tool generates these through the following underlying computational models.

Wind Modeling

The SHP Tool generates its wind fields using a highly efficient, linear analytical model for the boundary layer winds of a moving hurricane developed by Snaiki and Wu ([Snaiki17a], [Snaiki17b]). To account for the exposure in each New Jersey county, an effective roughness length (weighted average) of the upwind terrain is used based on the Land Use/Land Cover data reported by the state’s Bureau of GIS. In order to generate a wind field, this model requires the time-evolving hurricane track, characterized by the position (latitude, longitude), the central pressure, the radius of maximum winds, and the forward speed. While the model is fully height-resolving and time-evolving, for a given input hurricane scenario, the wind hazard is characterized by the maximum 10-minute mean wind speed observed during the entire hurricane track. This is reported at the reference height of 10 m over a uniform grid (0.85-mile spacing, 1.37 km) across the entire state in miles per hour, which is then accordingly adjusted for compatibility with the averaging interval assumed by the HAZUS Hurricane Damage and Loss Model. Since the wind speed (\(V(600s, 10m, z_0)\)) from the NJcoast SHP Tool is averaged over the time window of 1 hour, a number of standard conversions (see Standard Wind Speed Conversions) parse the wind speed to the 3-second and open-terrain PWS (i.e., \(V(3s, 10m, Exposure C)\)).

As the initial developer of this model has made the underlying code available for this testbed, users have two ways to engage this model to generate wind fields for this testbed: 1. Users can adopt the aforementioned default sythetic Category 5 scenario striking Atlantic City 2. Users can generate a custom storm scenario by providing the requied inputs into this linear 1. analytical model to generate a customized windfield for use with this testbed.

Wind fields described by either approach are then locally interpolated to the coordiantes associated with each footprint. The resulting 3s-gust peak wind speed (PWS) ranges from 178 mph to 191 mph given the simulated Category-5 hurricane event (Fig. 2.3.1.15). Because the SPH model tracks the maximum wind speed over the entire hurricane time history - so the inland cities are subjected to slightly higher wind speed than the coastal cities.

Fig. 2.3.1.15 Interpolated peak wind speed (3s-gust) for each asset in the inventory.

Storm Surge Modeling

Coastal hazard descriptions use the outputs of the aforementioned SHP Tool, which estimates storm surge and total run up due to the breaking of near-shore waves for an arbitrary hurricane scenario using surrogate modeling techniques ([Jia13], [Jia15]). The SHP Tool leverages the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) NACCS: North Atlantic Coastal Comprehensive Study ([NadalCaraballo15]), which contains over 1000 high-fidelity numerical simulations of hurricanes using the ADCIRC ([Luettich92]) storm surge model, coupled with STWAVE ([Smith01]) to capture the additional effects of waves offshore. It is important to note that the grid adopted for the NACCS execution of ADCIRC does extend into the riverine systems to capture the storm surge influx; however, the grid extensions up-river have limited extent and there was no explicit modeling of the riverine systems and interactions between those systems and the storm surge. The NACCS database was further enhanced with wave run-up simulations that capture the interaction of the waves with site-specific bathymetry/topography (2015 USGS CoNED Topobathy DEM: New Jersey and Delaware (1888 - 2014) dataset) to project the total run up inland, along transects spaced 0.5 km apart along the New Jersey coast. This results in a prediction of storm surge height at the USACE-defined save points along the New Jersey coast that are, on average, 200 m apart, with finer resolution in areas with complex topographies. The SHP Tool was executed for the testbed scenario to estimate the depth of storm surge above ground, geospatially interpolated to 110,000 nearshore locations at approximately 120 m spacing, accompanied by the Limit of Moderate Wave Action (LiMWA) and wet-dry boundary respectively defining the extent of damaging waves and inundation over land at each of the transect points. These are then interpolated to the location of the coastal parcels to express the property exposure to storm surge (Fig. 2.3.1.16). In the initial implementation, as demonstrated in this test, only the peak water depth (PWD) was considered, which will be used in the HAZUS Flood Damage and Loss Assessment.

Fig. 2.3.1.16 Interpolated peak water depth for each asset in the inventory.

Multiple Category Analysis (MCA)

Note that the resulting 3s-gust PWS values by this Category-5 hurricane is much higher than the design wind speed specified by ASCE 7-16 ([ASCE16]) for the Atlantic County which ranges from 105 mph to 115 mph. Since this extreme scenario bears a small likelihood, this testbed also scales the wind and flood water field down to lower categories to conduct the so-called Multiple Category Analysis to exam the building performance under different intense scenarios (Table 2.3.1.1) and were used later in the Verification Results (see Verification Results).

Hurricane Category |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Peak Wind Speed (mph) |

101 - 108 |

119 - 127 |

136 - 145 |

178 - 191 |

Peak Water Depth (ft) |

0 - 7 |

0 - 11 |

0 - 15 |

0 - 18 |

Users can access the synthetic wind field and storm surge inputs for the defined scenario, as well as the suite created for the MCA (Table 2.3.1.2).

Hazard |

Access Point |

|---|---|

Wind Field |

|

Storm Surge |

2.3.2. Historical Storm Scenario

Hindcast simulations of historical storm events are equally valuable, particularly when they are coupled with observations of damage and loss across an inventory. As such this testbed includes the option to use existing hindcast data from established community providers as input to the loss estimation workflow. New Jersey’s most notable storm event in recent history was Superstorm Sandy (2012). According to [NJDEP15] and [USDOC13], Sandy’s devastation included 346,000 homes damaged. The New Jersey State Hazard Mitigation Plan [NJSHMP] further notes that storm surge accounts for 90% of the deaths and property damage during hurricanes in this region. While Atlantic County was designated as a “Sandy-Affected Community” by FEMA and the State of New Jersey, the wind and storm surge intensities in the county were significantly less than those observed in the more northern counties. Nonetheless, these historical inputs are provided to demonstrate the workflow’s ability to support hindcast evaluations of damage and loss in actual storm events.

Wind Modeling

Hindcast wind fields for this event were made available by Peter Vickery and Applied Research Associates (ARA). Their hurricane model derives wind speeds based on numerically solving the differential equations of a translating storm and iteratively calibrating based on field observations over the weeks following an event. The ARA_Example.zip provides the peak 3-s gust peak wind speed field of Hurricane Sandy on a grid that can be directly used in the presented hurricane workflow, as visualized in Fig. 2.3.2.2 for Atlantic County.

Fig. 2.3.2.2 ARA 3-s gust peak wind speed (3-s gust at 10 m) in Atlantic County during Hurricane Sandy.

Alternatively, users can also use other available wind field resources. For instance, RMS Legacy Archive provides access to historical hurricane events including the Superstorm Sandy for an alternate description of the field. Similar to the ARA peak wind speed field, in order to run the workflow, users would first convert the data from other resources to the format as shown in ARA_Example.zip.

Storm Surge Modeling

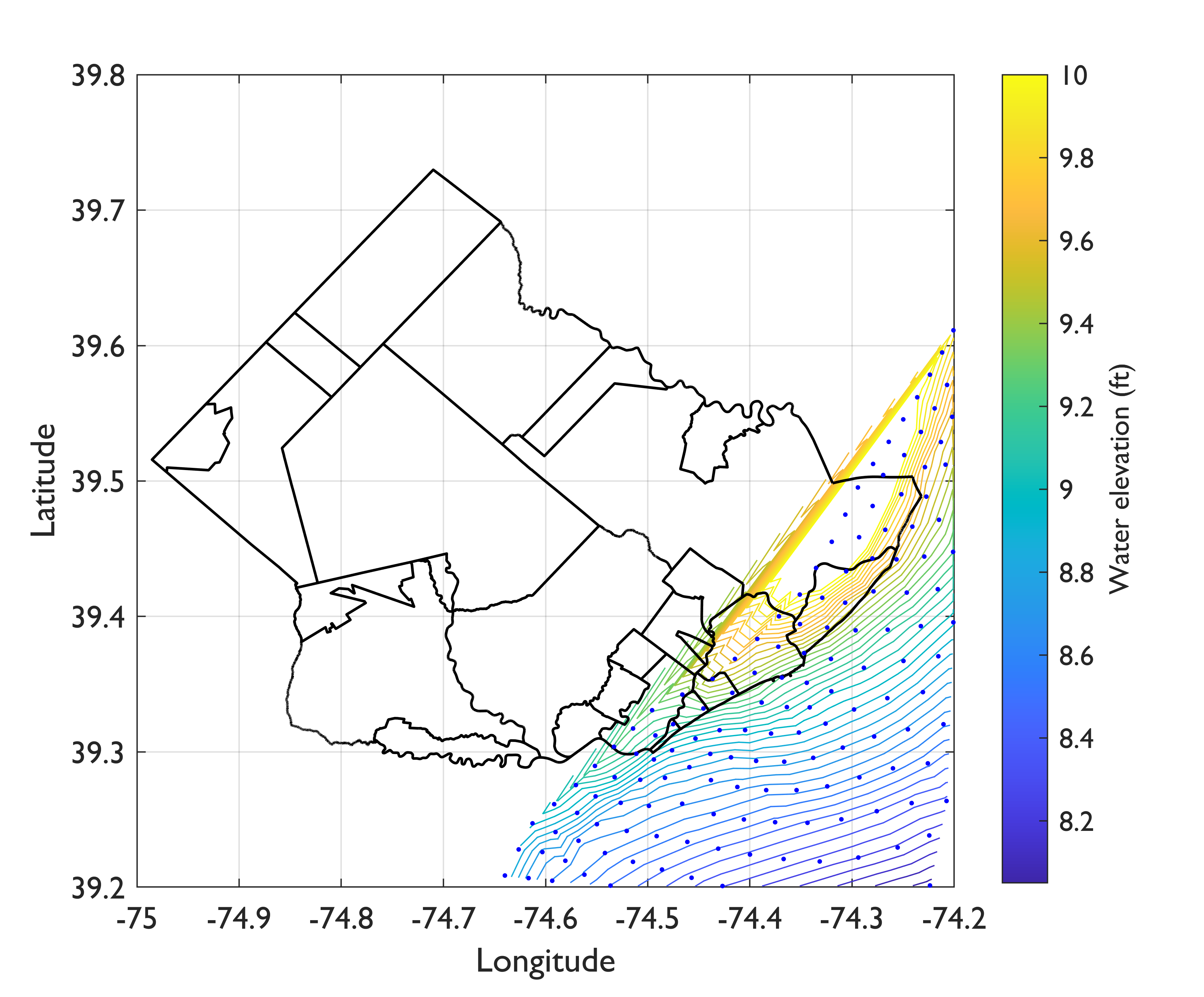

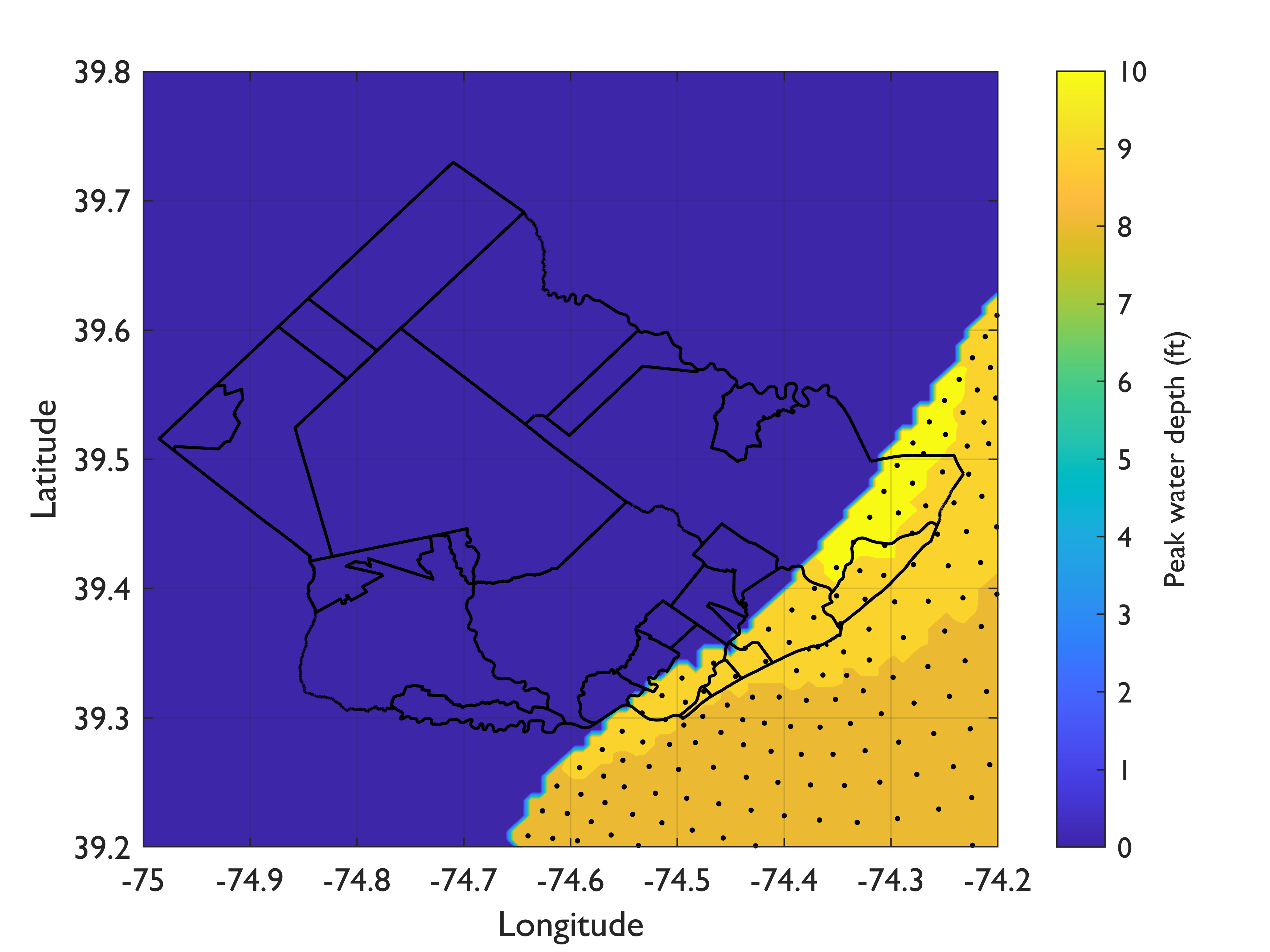

ADCIRC hindcast of Superstorm Sandy was generated by the Westerink Group at the University of Notre Dame and made available to the SimCentetr. Fig. 2.3.2.3 shows the peak storm surge from the hindcast. Note that the scope of the hindcast focused on the heavier-impacted regions of New York and Northern New Jersey, which were resolved with a finer mesh than more southern counties like Atlantic County, i.e., ~0.5 km (New York and Norther New Jersey) vs. ~3 km (Southern counties) between two closest nodes. In futher constrast with the NACCS ADCIRC runs referenced in Storm Surge Modeling, the grids adopted for the Sandy hindcast in this region of New Jersey did not extend into the riverine systems. Noting these limits of the simulation, peak water depth over land displayed in Fig. 2.3.2.5 assumes zero values in the rivering systems and at any point inland of the grid points shown in Fig. 2.3.2.4. The ADCIRC_Example.zip provides the peak water depth grid that can be used in the presented hurricane workflow.

Fig. 2.3.2.3 Simulated storm surge field of Hurricane Sandy by ADCIRC (by courtesy of Dr. Westerink).

Fig. 2.3.2.4 Simulated water elevation of Hurricane Sandy by ADCIRC (Atlantic County).

Fig. 2.3.2.5 Simulated water depth over land for Hurricane Sandy by ADCIRC (Atlantic County).

Hazard |

Access Point |

|---|---|

Wind Field |

|

Storm Surge |

- Snaiki17a

Snaiki, R. and Wu, T. (2017a) “Modeling tropical cyclone boundary layer: Height-resolving pressure and wind fields,” Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, 170, 18-27.

- Snaiki17b

Snaiki, R. and Wu, T. (2017b) “A linear height-resolving wind field model for tropical cyclone boundary layer,” Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, 171, 248-260.

- ATC20

ATC (2020b), ATC Hazards By Location, https://hazards.atcouncil.org/, Applied Technology Council, Redwood City, CA.

- NJCoast20

NJ Coast (2020), Storm Hazard Projection Tool, NJ Coast, https://njcoast.us/resources-shp/

- ASCE16

ASCE (2016), Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures, ASCE 7-16, American Society of Civil Engineers.

- ESDU02

Engineering Sciences Data Unit (ESDU). (2002). “Strong winds in the atmospheric boundary layer—Part 2: Discrete gust speeds.” ESDU International plc, London, U.K.

- Jia13

Jia G. and A. A. Taflanidis (2013) “Kriging metamodeling for approximation of high-dimensional wave and surge responses in real-time storm/hurricane risk assessment,” Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, V(261-262), 24-38.

- Jia15

Jia G., A. A. Taflanidis, N. C. Nadal-Caraballo, J. Melby, A. Kennedy, and J. Smith (2015) “Surrogate modeling for peak and time dependent storm surge prediction over an extended coastal region using an existing database of synthetic storms,” Natural Hazards, V81, 909-938

- NadalCaraballo15

Nadal‐Caraballo N.C, J. A. Melby, V. M. Gonzalez, and A. T. Cox (2015), North Atlantic Coast Comprehensive Study – Coastal Storm Hazards from Virginia to Maine, ERDC/CHL TR-15-5, U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, Vicksburg, MS.

- Luettich92

Luettich R.A, J. J. Westerink, and N. W. Scheffner (1992), ADCIRC: An advanced three-dimensional circulation model for shelves, coasts, and estuaries. Report 1. Theory and methodology of ADCIRC- 2DDI and ADCIRC-3DL, Dredging Research Program Technical Report DRP-92-6, U.S Army Engineers Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, MS.

- Smith01

Smith J.M, A. R. Sherlock, and D. T. Resio (2001) “STWAVE: Steady-state spectral wave model user’s manual for STWAVE, Version 3.0,” Defense Technical Information Center, US Army Corps of Engineering, Vicksburg, MS.

- USDOC13

U.S. Department of Commerce (2013), Hurricne Sandy: Potential Economic Activity Lost and Gained in New Jersey and New York.

- NJDEP15

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) (2015), Damage Assessment Report on the Effects of Hurricane Sandy on the State of New Jersey’s Natural Resources.

- NJSHMP

State of New Jersey Office of Emergency Management (2012), The State of New Jersey’s Hazard Mitigation Plan, http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/2012-mitigation-plan.shtml.